Slovakia People’s Party Our Slovakia gave Europe its first neo-Nazi governor and built on fear, distrust and discontent to take its first seats in Slovakia’s parliament last year. It is poised for new gains in 2017.

Tomáš Nociar

A decade has passed since uniformed young men and women staged infamous marches in several Slovak towns, reminding many Slovaks of paramilitary groups like the Hlinka Guard of the interwar period. The marches were arranged by Slovak Togetherness (Slovenská pospolitost), a marginal extreme right-wing group led by Marián Kotleba, and were the source of his first publicity.

Slovenská pospolitost marching. Marián Kotleba is in the middle of the front row. Photo: Matúš Tremko, under Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 license.

In 2013, Kotleba surprisingly won the second round of gubernatorial election in the Banská Bystrica region of central Slovakia. As a result, this controversial politician, previously known for his part in street clashes with the police, became the first elected regional governor with a neo-Nazi background in post-war Europe. The election breakthrough in Banská Bystrica was a sign of things to come, including the success of Kotleba’s People’s Party Our Slovakia (Ľudová strana Naše Slovensko, LSNS) in last year’s elections. His unexpected regional success could well be seen as a warning from the voters, since the extreme right’s crossing of a political threshold by winning important offices was a slap in the face to Slovakia’s political establishment. Kotleba’s party took more than 8 per cent of the vote, opening the door to parliament by taking 14 seats.

The roots and extremism of Kotleba’s party

2014: Banner at the Banská Bystrica administration building put up by Kotleba, ‘Yankees go home! Stop NATO!’ Photo: Ján Krošlák, SME, under Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 license.

Kotleba’s People’s Party Our Slovakia was formed in 2010 as a direct successor to his former political project, Slovak Togetherness-National Party, the first and only political party in Slovakia’s short history to be dissolved by the Supreme Court. The party was found to have failed to comply with the constitution. As a relatively young party, LSNS is bit of an exception to the rule when looking at the current rise of the far right in Europe.

Most of the successful far-right parties in Europe have a mixture of nativism, authoritarianism and populism at the core of their political agenda, belonging to what the Dutch political scientist Cas Mudde calls the “populist radical right”. Kotleba’s LSNS, however, is the third example of a successful extreme right party gaining seats in the national parliament of an EU member state, after Greece’s Golden Dawn and – arguably – Hungary’s Jobbik. 1

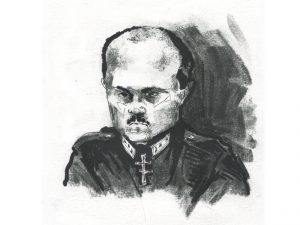

Illustration: Marijke Strømmen

What makes Kotleba’s party more extreme? Several authors in the field distinguish between successful new populist parties and less attractive old extreme right parties, associated with fascism. Italian political scientist Piero Ignazi points out how the latter group is not only characterized by nativism and authoritarianism, but also by an anti-democratic nostalgia for interwar fascism, expressed through references to the myths, symbols and slogans of fascism, or to fascist ideology in general. With Kotleba’s party in mind, several examples illustrate these sympathies towards fascism. In addition to nostalgia for the wartime Slovak state, the most striking example may be the party’s 2012 electoral manifesto, entitled 14 Steps for the Future of Slovakia and our Children. If the title sounds familiar, it is because of the infamous neo-Nazi slogan known as the 14 words: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.” The similarity speaks for itself, and the inspiration appears obvious.

More recent examples can be found by taking a brief look at the mindset of some party members and activists. These include three of the party’s candidates for parliament: Rastislav Rogel, the frontman of the infamous Slovak neo-Nazi band Juden Mord (Jew Murder) and a man who questions the holocaust and encourages the use of “Sieg Heil” in song lyrics; Marián Mišún, known for his anti-Gypsy rhetoric, including his text “The final solution to the Slovak Gypsy problem!” (“Konečné riešenie slovenského cigánskeho problému!”); and Marián Magát, Slovakia’s most notorious admirer of Hitler and the leader of a neo-Nazi paramilitary group called Action Group Resistance. Magát’s 88th position on the list of candidates can hardly be seen as a coincidence in this context, since it is well known that the number 88 is popular in the neo-Nazi movement as a code for “Heil Hitler” since “H” is the eighth letter of the alphabet.

While none of these candidates made it into the parliament, another one did: the youngest parliamentarian elected, Milan Mazurek, 22, known as a Holocaust denier after he stated on social media: “I do not advocate any regime, but regarding the Third Reich we only know lies and fairy tales about 6 million Jews and soap. Nothing but lies are taught about Hitler.”

In fact, Kotleba’s family business also demonstrates a tendency towards fascism and extremism. Together with his two brothers – also party candidates in last year’s election – he runs a street-wear shop called KKK – English fashion (KKK – Anglická móda) that has been a subject of police investigation for selling neo-Nazi materials. When asked if KKK stands for Ku Klux Klan, the reply was that it symbolizes the three Kotleba brothers.

Using the populist agenda

Advertising a party event. The title reads: “Do not believe the media! Come and hear the truth!”.

In spite of the examples above, it would be inaccurate to claim that Kotleba’s rise is a sign that society is becoming fascist, or that Slovakia is reverting to the politics of the 1930s. The party and its leader have succeeded despite their failure to shed their fascist legacy, something that other European far-right parties have done. The idea of abandoning democracy and issues like anti-Semitism are no longer at the core of the party’s agenda, unlike in Kotleba’s previous, unsuccessful political project. Instead, they send signals to those who are more extreme that, while the party strives to present itself as more moderate, it is still made up of the same extreme right believers.

Now, however, typical party slogans target the political elite and the Romani people, sometimes called Gypsies, with phrases like, “We will take care of the thieves with ties, as well as parasites in settlements.” Building an image as the defenders of the people against a corrupt elite and ethnic minorities has proven more effective in drawing voters. From this perspective, Kotleba’s party is more similar to such parties as the French Front National and the Italian Lega Nord than to interwar fascists or current neo-Nazi movements. In a nutshell: People’s Party Our Slovakia is a party led by an extreme right-wing activist who has turned to a xenophobic, populist agenda to attract voters.

Kotleba’s impact on Slovak politics

The rise of right-wing extremism in Slovak society became a hot topic after the March 2016 elections. Most of the post-election debates dealt with the presence of an extreme right-wing party in parliament and how mainstream parties should respond: involve it or ignore it in the legislative process?

Unfortunately, the debates largely missed the point that the rise of the far right is first and foremost a symptom of a failure in mainstream politics, an observation confirmed by exit polls that identified social problems and corruption among the key motivations for Kotleba’s voters. A more recent survey suggests that most voters believe politicians do not work for the public interest but for their own and their sponsors’ benefit. This leads to a rise of general distrust in the political establishment, as well as increased scepticism about democracy, with a quarter of Slovaks saying they would welcome dictatorship. These views are most popular amongst those with the lowest levels of education and income. Another risk group is young people, for whom Kotleba’s People’s Party Our Slovakia is the most popular choice.

Milan Mazurek, here holding a speech at the socalled Independence March in Warszawa, Poland, where he was introduced by a speaker from the National Radical Camp, which sees itself as the ideological descendant of the pre-WWII ultranationalist and anti-Semitic group by same name. Photo: Screenshot from a video of the speech released on YouTube.

Amidst this public mood, Kotleba and his party can afford to sit back and wait. According to the most recent poll, support for LSNS has risen from 8 to 11 per cent since the elections. Another strategy of the party has been to act as an anti-establishment provocateur in order to gain media attention. An illustrative example is the nomination of the 22-year-old Mazurek for the parliamentary human rights committee. Mazurek is known not only for Holocaust denial but also for shouting expletives about Allah and “Allah is Satan” at a Muslim family who was attacked by rock-throwing extremists during an anti-immigrant demonstration in Bratislava.

Other examples of the party’s recent anti-establishment and populist initiatives include proposals to remove the system of state funding of political parties from the national budget and to cut the number of members of parliament. They also want to define NGOs receiving international grants as foreign agents, a legislative proposal similar to those applied by the illiberal governments of Russian President Vladimir Putin and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. After Brexit, the party also launched a petition for a referendum on Slovakia leaving the European Union. The most publicized post-election provocation, however, was when the party questioned the ability of the state to protect its own citizens and the establishment of party-run, vigilante “train patrols”, led by MP Peter Krupa, who drew attention for carrying a gun in parliament. The ostensible goal of the patrols was to ensure the safety and protection of passengers against potential Romani “troublemakers”. However, the party also introduced it as a first step towards the establishment of a militia. Slovak media immediately started to speculate that the party’s state funding was being used to achieve this goal.

In other words, Kotleba’s success in the parliamentary elections led to a bizarre situation, which – somewhat provocatively, of course – might be called state-sponsored extremism. On one hand, the party is regularly described as an extremist group in official government reports. On the other hand, the election results made it eligible for state funding. Within the parliamentary term of four years, the party is expected to receive 5.2 million euros in all from the national budget.

Responses and counterstrategies

The party’s presence in the national parliament also triggered the adoption of several measures that supposedly counter extremism.

The first was the creation of a coalition government between parties covering a broad political spectrum. The social democratic Smer, the conservative party Sieť, the inter-ethnic (Hungarian-Slovak) party Most-Híd (formed by dissidents from the Party of the Hungarian Coalition in 2009 and dominated by ethnic Hungarians) and by the Slovak National Party, formerly seen as both far right and anti-Hungarian, are all part of the coalition that was presented by its leaders as a barrier to extremism.

Following an election campaign dominated by the refugee issue, the strongest party, Smer, also started to attack Romani and so-called political correctness, an obvious attempt at winning back former social democratic voters by adopting some of the rhetoric of the far right. Other parties, most notably the liberal Freedom and Solidarity party (Sloboda a Solidarita), have also tried this approach.

Another kind of anti-extremism measure was part of a Ministry of Justice initiative to amend anti-extremist legislation with new classifications of racially motivated hate crimes. The most significant change was to transfer the issue of extremist criminality from the district courts to the Specialized Criminal Court. However, in a situation where more than 200,000 people in a country of five million citizens vote for what might be seen as an extreme-right party, there are serious doubts that any kind of legal measures can serve as an effective tool. Kotleba’s party is mainly a political problem, and should primarily be fought politically.

The first chance to do so comes in regional elections later this year. Taking into account the recent results of far-right candidates in countries like France or Austria, however, the strategically unfortunate initiative of the governing coalition to change the electoral system from a two-round system to a one-round system could easily lead to another electoral victory for Kotleba, even though he is still an unpopular and distrusted politician for most Slovaks. The last attempt to defeat Kotleba failed, providing strength to the Kotleba phenomenon. The next attempt could easily become a farce, further strengthening the Slovak extreme right.

Footnote:

- Later, Golden Dawn’s sister party – the National People’s Front in Cyprus – also entered parliament, a story largely overshadowed by the second round of presidential elections in Austria, which took place at the same time as the Cypriot parliamentary elections. ↩

Print Friendly

Print Friendly

You say: ” is the third example of a successful extreme right party gaining seats in the national parliament of an EU member state, after Greece’s Golden Dawn and – arguably – Hungary’s Jobbik.

And what withh FN in France, VB in Belgium, FPÖ in Austria, UKIP in England, PVV in the Netherlands, etc… or do you differentiate extreme-rights light and extreme-right regular?..And when becomes light regular?