ANALYSIS: Cross-referencing the videos published by the US-led coalition and by A’maq, the Islamic State’s most important auxiliary media wing, can provide us with insight into how civilians are caught in the crossfire.

Christiaan Triebert

Since the international air campaign started in Syria and Iraq, both the US-led coalition’s official media channels and Islamic State’s (IS’s) most important auxiliary media wing, the Aʿmaq News Agency, have published videos of or related to airstrikes. The hundreds of videos published by the coalition’s official YouTube channel or by Aʿmaq present on the one hand a clean and surgical air campaign against military targets and on the other the deaths of innocent civilians and the destruction of hospitals and infrastructure. If one understands propaganda as information used to promote a political cause or point of view, both the coalition’s as Aʿmaq’s videos can be labelled as such. But is there more to those videos?

The videos only account for a minor part of all coalition airstrikes in Syria and Iraq, given that, as of December 2016, the coalition has conducted 16,725 airstrikes, roughly twenty strikes per day.1 However, some incidents were filmed and published by both the coalition and Aʿmaq, thus portraying the aerial as well as the ground perspective of the same strike. Before highlighting several such events, grouped alongside the type of (claimed) target, the international airport campaign and Aʿmaq will be discussed.

In reaction to the rapid territorial gains made by IS in 2014 and its reported human rights abuses, many states started to intervene militarily against the group in Syria and Iraq. Since December that year, those military efforts “to degrade and destroy” IS have been coordinated under the banner of the Combined Joint Task Force, established by the United States (US) and more commonly referred to as the coalition.

As the coalition’s Operation Inherent Resolve began, it started uploading videos showing such airstrikes against alleged IS targets on DVIDS, an official US defence website, as well as on its official YouTube channel since April 2015. Neither civilians nor militants can be seen in these videos. Instead, the videos present a clean and surgical war against military targets such as buildings and vehicles. Over 100 such airstrike videos have been published by the coalition in two years.

A screengrab of a typical coalition airstrike video showing an alleged IS truck speeding along a desert road near Qayyarah, Iraq, and then being blown up by an airstrike. A text such as “You can run, but you can’t hide” has only been added once to a video by the coalition.

Half a year after the first coalition videos came out, Aʿmaq started publishing videos showing the alleged aftermath of these airstrikes. What they showed were not vehicles or military targets, but destruction of infrastructure and education, and civilian deaths. This perspective neatly fits into the narrative IS takes in its official media releases, Pieter Nanninga says. He is an assistant professor and expert on jihadist media at the University of Groningen and an expert on jihadist media.

“Footage of airstrikes showing the targeting of non-military targets such as hospitals, schools, banks, and infrastructure is part of IS’s message of a war against Muslims that is being waged, emphasizing the suffering of Muslims and IS’s role as the defenders thereof,” Nanninga says. Claiming to show the aftermath of such airstrikes, the videos are used to illustrate IS’s perspective of the barbaric nature of the West, as well as its hypocrisy, he adds. While the West “preaches” human rights, freedom, and democracy, it has been targeting Muslims for decades.

The coalition’s airstrikes are presented, in addition, as a symbol of the West’s cowardliness and inherent weakness, Nanninga argues: “Whereas IS fighters are willing to sacrifice their lives for their cause, the enemy is killing civilians by pressing a button. This message plays upon feelings among Muslims who identify with the suffering of their fellow believers and want to assist their brothers and sisters in need.”

Aʿmaq first appeared during the Siege of Kobanî in September 2014, behaving “somewhat like an embedded state agency”, Nanninga says, “mainly producing news reports and short, lightly edited videos on IS’s battlefield operations”. Initially, Aʿmaq distributed its materials mainly on Twitter, Nanninga says, but as authorities have waged a digital crackdown of IS’s online presence, Aʿmaq has increasingly shifted to Telegram and other variable website addresses from countries such as Tokelau, Mali, and Equatorial Guinea. Telegram is still being used as one of the main channels to spread Aʿmaq’s information, and from there it travels to Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Nanninga: “Typically, these reports generate much less attention than, for example, IS videos and magazines, but in several cases they are being shared massively by IS supporters as well as mainstream media and academics.”

The logo of the Aʿmaq News Agency.

While propaganda output by belligerents is nothing new, Aʿmaq’s veneer of objectivity represents for that very reason an innovation in jihadist media strategies, according to Nanninga. “Whereas jihadist groups usually relied on a single media producer, such as Al-Qaeda’s Al-Sahab, IS has established several media groups, each with its own functions and target audience.” And Aʿmaq is very good in spreading its propaganda on social media, as well as in conventional media.

The media organization may have been created or allowed to develop in a bid to create a source of information that is still basically controlled by IS, Rukmini Callimachi writes in the New York Times, thereby “giving [IS] more of the appearance of legitimacy”. In line with that veneer of objectivity, Aʿmaq has consistently adopted a conservative approach to casualty estimates related to coalition airstrikes, Chris Woods, the director of Airwars, notes. His organization monitors international airstrikes in Syria, Iraq, and Libya. “In fact, Aʿmaq often reports lower casualty numbers than other local sources. This may lend credibility to IS’s output for some, by appearing to portray them as a ‘moderate’ voice,” Woods suggests.

“Its video news reports not only closely resemble conventional news packages, but are also then broadcast by mainstream news organizations as a reflection of a claimed event,” Woods continues. This can be problematic, as it may lead to an IS-dominated perspective of particular events – specially since IS has fiercely suppressed independent monitors and journalists. Woods: “This is compounded by the coalition’s general refusal to engage via social media on specific allegations – in effect leaving the digital field to the enemy.”

Since November 2015, Aʿmaq has incorporated themes other than battlefield operations into its video productions, including footage of “daily life” inside the caliphate, as well as the results of airstrikes. “Well-known examples are the reported targeting of a wedding convoy in Raqqa in January 2016 and two videos featuring John Cantlie commenting on airstrikes that targeted media points in Mosul and Mosul University in March and July 2016,” Nanninga says. Cantlie was kidnapped in 2012 and has been held since. “Those Cantlie videos, as well as the ones in which Aʿmaq claims attacks in the West as being carried out by ‘caliphate soldiers’ clearly shows its connection to the group.”

While it easy to dismiss Aʿmaq’s videos as pure propaganda, even the US has admitted that civilians have been killed due to coalition airstrikes. However, the US tally of 119 civilian fatalities is still far below what Airwars’ researchers estimate to be a minimum casualty figure: 1,900 deaths. That would represent one civilian death per eight airstrikes. While the videos need to be treated with significant caution, Aʿmaq’s footage can have some value among other open source materials, Airwars’ Woods believes. “On occasion it can be the only source of visual information.”

A screengrab of one of the websites used by the Aʿmaq News Agency. There are different website sections for videos, news reports and infographics, which are updated daily.

Woods adds that IS has invested significant effort in killing or suppressing independent local casualty monitors and reports. “This makes it impossible to challenge the veracity of many of its claims. For example, the credibility of reported eyewitnesses is not provable [and] footage reportedly depicting a scene cannot be independently matched.”

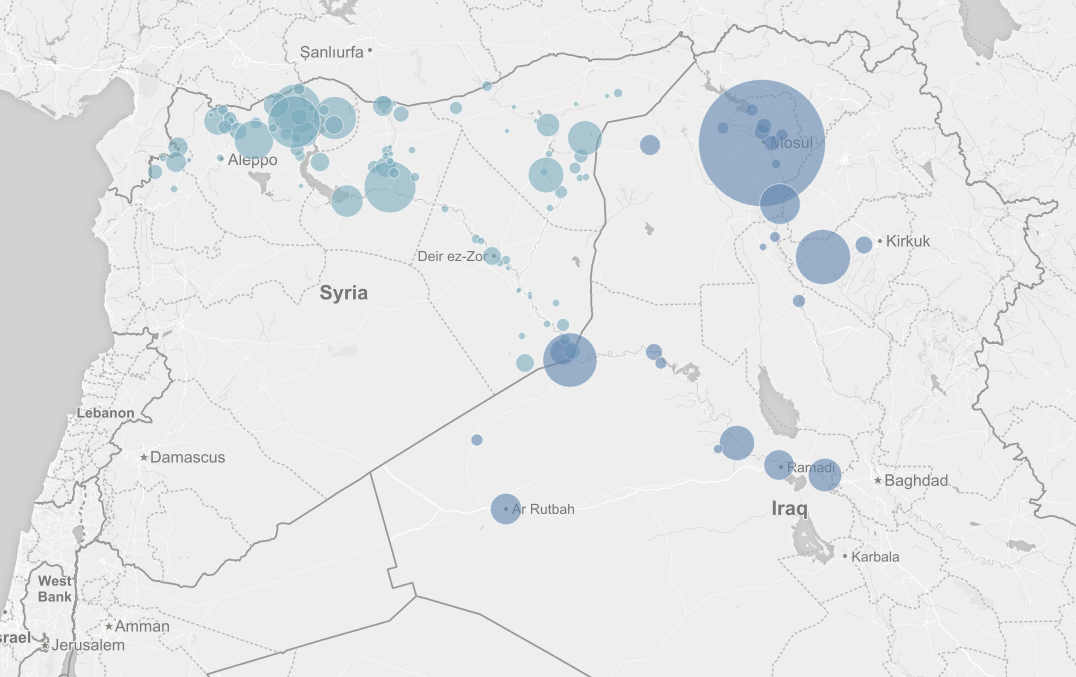

Locations of alleged and confirmed civilian casualties due to coalition airstrikes, as mapped by Airwars. Manbij in Syria and Mosul in Iraq have especially witnessed a large amount of fatalities, as the circle shows.

Aʿmaq’s airstrike aftermath videos have become more important in IS media over the last year, Nanninga has noticed. “This should be understood in the context of IS’s recent setbacks in the fields of warfare and, particularly governance. By showing footage of targeted hospitals, schools, banks, and infrastructure, IS blames the West for its current troubles in the field of governance.” In other words, the theme of victimhood has become more important, implying that while IS tries its utmost to build a well-functioning state, it is being opposed in its efforts by the rest of the world, Nanninga says.

It is hard to say anything about the airstrikes and their aftermath based on either Aʿmaq or the coalition’s videos, given IS’s suppression of independent observers and journalists and the coalition’s rough demarcations of what was struck and where. This analysis aims to provide a better understanding of what was (allegedly) struck, and where, by corroborating and triangulating the open source information available. It thus links an aerial perspective of an airstrike to a ground perspective.

Airstrikes on infrastructure

The moment of airstrike impact on the Qayyarah Bridge in August 2014. Courtesy of “إنتفاضة أحرارالعراق”, via YouTube.

Many bridges within IS-held territory have been targeted in recent years, such as the Omar bin Abdul Aziz bridge in Ramadi (18 November 2015), the Hurriyah bridge in Mosul (21 January 2016; 16 October 2016), the Mayadeen bridge (28 September 2016), and the Al-Asharah bridge (1 October 2016 – though reports conflict as to whether the airstrikes were Russian or coalition). Several of those bridges were repaired afterwards by IS’s civil services, as shown in Aʿmaq videos and confirmed by satellite images.

An Royal Air Force strike on the Qayyarah bridge. Courtesy of the UK Ministry of Defence.

A striking example of a bridge that was bombed and repaired more than once is the Qayyarah bridge, named after the adjacent town, about 30 km south of Mosul. The town fell to IS in June 2014 but was recaptured in August 2016. Linking the east and west banks of the Tigris River, the bridge was of considerable strategic importance for IS when it still held the town, and still is for the anti-IS forces taking part in the Battle for Mosul. During the period the bridge was in IS’s hands, it was bombed no less than six times.

The first time the bridge appears to have been bombed was in August 2014, an attack caught on camera on the ground.

A few months later, in December 2014, reports emerged that the Qayyarah Bridge had been rendered unusable by IS to slow down approaching Peshmerga forces. This could not be independently confirmed.

Then, in March 2016, two more separate airstrikes hit the Qayyarah Bridge: the first on 7 March, according to Aʿmaq videos, which showed small damage at the bridge, and the next on 8 March, rendering the bridge unusable. Meanwhile, Aʿmaq published a video showing civilians going by boat from one bank of the Tigris to the other.

Satellite imagery, courtesy of Planet Labs, shows the Qayyarah bridge at several times in 2016. The damage from airstrikes and repair efforts are both clearly visible on the images.

Efforts “to open resupply routes” of the Qayyarah bridge were destroyed by “two direct hits from Paveways”, and three engineering vehicles were also bombed by the coalition, as a video from the UK’s Ministry of Defence shows.

The bridge was repaired – again – as is visible in a video of a coalition airstrike on 24 March, which, instead of damaging the sides of the bridge, takes out the middle.

All of these incidents can be confirmed by satellite imagery, provided courtesy of Planet Labs, as they show the patterns of damage described above.

As of November 2016, the bridge remained badly damaged, but Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) have constructed a temporary bridge south of Qayyarah to link up with forces in Hajj ‘Ali, as is shown in 27 November 2016 satellite imagery of Planet Labs.

Two annotated stills from the coalition airstrike video showing the strike of 24 March 2016, from the air. It can be seen that the earlier damage done by the 4 March strike has been provisionally repaired. Courtesy of the CJTF-OIR, via YouTube.

Water infrastructure, too, plays a significant role in Syria and Iraq, and has been deliberately targeted in the war by several actors. The conflict in Syria has caused “indescribable harm” to Syria’s water infrastructure, a November 2014 report claims, and it seems it has only gotten worse since.

A still from an Aʿmaq video showing the Abu ‘Amr water-pumping station that was allegedly bombed by the coalition.

Aʿmaq has published three videos regarding (alleged) airstrikes on water infrastructure, the first one on 17 November 2015 against a water-pumping station for irrigation in the small village of Abu ‘Amr in Syria’s Deir ez-Zor province. In-depth research published on Bellingcat could not confirm that it was indeed a coalition airstrike that caused the damage.

The Russian Air Force targeted the Al-Khafsa water treatment plant, as a video published by its own YouTube channel shows.

An incident worth highlighting is the bombing, in November 2015, of the most important water treatment plant of Aleppo province. While a Syrian news agency referred to the coalition as the perpetrator of the bombing of critical water infrastructure, it was the Russian Ministry of Defence that published a video showing that it was the Russians who bombed it, while claiming it was an oil refinery. A similar alleged Russian bombing of critical water infrastructure happened in January 2016 in Ar-Raqqah province. Interestingly, both of the facilities were staffed and operated by engineers paid by the Syrian government, thus leaving questions as to why Russia would bomb these facilities.

Alleged airstrikes on mosques

Other than airstrikes on infrastructure, Aʿmaq has shown alleged airstrike aftermaths at or near mosques, such as the Omar Ibn Al-Khattab mosque in Mosul (3 November 2015), the Green Mosque in Qayyarah (1 December 2015), the Hassan mosque in Fallujah (27 January 2016), the Omar Al-Farook mosque in Kubaysah (9 March 2016), the Al-Nur mosque in Ar-Raqqah (1 April 2016), the Raqeeb mosque in Fallujah (23 May 2016), the Mudallal mosque in Fallujah (28 May 2016), and the Rawda Mohammidiyah mosque in Mosul (6 October 2016).

The coalition claims to be avoiding striking locations such as mosques, as was evident in a France 2 documentary that peeked into France’s Directorate of Military Intelligence and showed schools, a hospital and mosques marked in yellow.

However, remnants of weapons used by coalition air forces were filmed at the alleged location of an airstrike, Aʿmaq videos show. An example is the remnants of a fin for an MK82 guided bomb, with identification number 96214 ASSY 83776[XX], shown at what appears to be a bombed mosque in Kubaysah, Iraq. The possibility that these remnants were planted or filmed elsewhere could not be excluded by independent means. Satellite imagery of TerraServer captured after the incident showed major damage at the mosque.

France’s Military Intelligence marks civilian objects in their identifying of IS targets. Image is a still from a France 2 documentary by Complément d’Enquête on France’s war against IS.

An airstrike on a building on the compound of the Rawda Mohammidiyah mosque has also been filmed by Aʿmaq. The mosque itself appears to be untouched, but a building adjacent to the mosque – most likely a Quran school – was destroyed. This can be confirmed by satellite imagery taken after the incident. Whether IS used the school for other purposes could not be confirmed.

The most striking incident was a confirmed airstrike on a vehicle parked just outside of the Al-Nur mosque in Ar Raqqah. Shortly after the airstrike, Aʿmaq published a video of the aftermath, saying civilians had died and showing damage at the street and the mosque by a US drone strike. Whether or not it was a drone strike, the US admitted on 9 November 2016 (the day after the US presidential election) that it was indeed its airstrike and that three civilians had died “after entering the target area after the aircraft released its weapon”.

The exterior and interior of the Al-Nur mosque in Ar-Raqqah, clearly showing the destruction left by a US airstrike.

The individuals in one car were probably high-value targets, but their proximity to other cars caused the civilian casualties. As Samuel Oakford notes on Airwars, attacks on religious places are generally prohibited by the laws of war. The airstrike was not pre-planned but “a dynamic strike that strictly adhered to all our civilian casualty processes and complied with the Law of Armed Conflict”, a CENTCOM spokesperson told Airwars.

“Unfortunately, civilians appeared in the target area after the weapon was released and we did not have an opportunity to ‘shift cold’ the weapon elsewhere.” The US military calculus in determining whether to execute such a controversial airstrike remains open to question, Oakford concludes. The target was on a narrow urban street around Friday prayers, so it was likely that civilians would be present.

Alleged airstrikes on healthcare

Aʿmaq has accused the coalition of striking targets related to health care on four occasions: an ambulance in Hawija, Iraq (26 January 2016), an autism care centre in Mosul, Iraq (1 June 2016), a dental care facility in Mosul, Iraq (4 April 2016), and a hospital in Al-Qaim, Iraq (7 October 2016).

A destroyed ambulance allegedly due to a coalition strike in Hawija, Iraq, 26 January 2016

The ambulance in Hawija appears to have been close to the strike impact location, and not a direct target. However, according to multiple reports, this alleged coalition strike resulted in at least 13 civilian deaths. Responding to a request for clarification about possible Royal Air Force (RAF) involvement, the UK Ministry of Defence told monitoring organization Airwars that “after extensive research, we can confirm that there was no UK involvement” in the incident.

The existence or destruction of the autism care centre in Mosul could not be confirmed. Local and national sources, such as Mosul Eye and NRN News, did report that civilians were killed alongside IS fighters due to coalition airstrikes. The coalition reported several strikes in Mosul that day. No reports other than Aʿmaq’s could be found mentioning the dental care institution in Ar-Raqqah or the hospital in Al-Qaim.

The only incident which is somewhat health related, and of which videos have been published from both sides, is one involving the Nineveh Pharmaceutical Company, located about 10 kilometres northeast of Mosul. The facility included units that produced capsules, tablets, ointments, syrups, ampoules, eye and oral drops, sprays and sanitizers, according to a March 2014 World Bank Group report on the facility. It was bombed on 14 September 2016.

Aʿmaq dubbed the facility, once operated by pharmaceutical company MS Pharma, as “the only medicine factory in Mosul” and said it was struck by American planes. Fire trucks can be seen extinguishing smouldering heaps of rubble as a drone goes up in the air to film the airstrike’s aftermath.

A still from an ʻAmāq video showing the aftermath of coalition airstrikes on a pharmaceutical company north of Mosul, Iraq.

The US Central Command claimed the facility was a “chemical weapons factory” which was massively bombed by 12 different aircraft, including F-15s, A-10s, and a B-52. A video of the bombardment by the B-52, also known as a Stratofortress, was published online. Another video was of the same airstrike on the building complex – “a pharmaceutical plant complex [that was being turned] into a chemical weapons production facility” – was published on DVIDS.

Was the facility still that of a pharmaceutical company, or was it being used as a chemical factory? Clashes between Peshmerga forces and IS fighters were reported in July 2014 at the plant, shortly after the city of Mosul fell to IS. A few months later, in December 2014, the plant had stopped operating, according to the Nineveh provincial health department. Given those fights and its strategic location, it is thus questionable whether the medicinal plant was still being operated as such. The pharmaceutical complex was reportedly captured by Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) on 25 October 2016.

Other industrial sites in Mosul have also been heavily targeted by coalition strikes, satellite imagery and videos from inside the city have shown. This may create several additional environmental and health risks as the Battle for Mosul rages on.

The pharmaceutical complex was only one of many industrial sites that have been targeted by coalition airstrikes. Several of the Aʿmaq videos can be corroborated with official airstrike videos by the coalition. One site that was targeted on 20 September 2015 is an alleged wheat plant in Mosul’s Wadi ʿEgab industrial district. The coalition published a video showing the airstrike.

A soft drink and ice factory complex, locally known as the Pepsi plant, was allegedly targeted by a coalition airstrike on 14 or 15 March 2016. The footage could be geolocated to a factory in Mosul’s Al-Zinjili district, and TerraServer satellite imagery confirmed massive destruction at the site.

A still from an Aʿmaq video showing the aftermath of an alleged coalition airstrike on what the news agency claimed was an operating soft drinks company.

A local source told NRN News that the plant had been defunct for a long time and that there were no workers or employees anymore. It had turned into a laboratory building, the source claimed. The coalition said it struck two factories for vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIED) in Mosul on the same date, which likely refers to the Pepsi plant.

Days later, on 24 March, a milk factory of Mosul Diary in Mosul’s Al-Rashidiyah district was allegedly targeted by a coalition strike. While geolocation and cross-referencing of the Arabic name indeed confirms this is the place of a milk factory, it cannot be determined whether the factory was operational for its intended purpose. No civilian casualties were reported; CENTCOM stated it had “destroyed two ISIL assembly areas” in Mosul. Earlier, on 17 November 2015, Aʿmaq claimed the coalition had struck a different milk (and ice) factory elsewhere in the city.

A still from an Aʿmaq video showing the aftermath of an alleged coalition airstrike on a milk factory in Mosul, Iraq. Aʿmaq claimed the facility was operating as such.

Other industrial facilities allegedly targeted by the coalition, according to Aʿmaq, are a construction company in Mosul (13 January 2016), the Badoosh cement factory in Iraq (6 August 2016), a granary near Shirqat, Iraq (6 August 2016), warehouses of the electricity committee in Mosul (14 August 2016) – to name a few. The current or former intended purposes of those facilities does not necessarily mean they have been used as such during IS rule.

A still from an Aʿmaq video showing the aftermath of an alleged coalition airstrike on the Badoosh cement factory in Iraq.

Many of the industrial sites that were bombed were said to be weapons factories, and most of these locations were in industrial areas. One significant “weapons factory” claim that was made by the coalition actually referred to attacks on several buildings on the University of Mosul campus, on two different days in March 2016. By cross-referencing the coalition’s videos of the airstrikes, and before and after satellite imagery, the locations bombed – such as the Presidency and the College of Electric Engineering – could be established using a map of the university campus. The Pentagon claimed in a statement to VICE News that these “buildings the coalition struck have been turned into a headquarters building by [IS] since late 2014 or early 2015”. While this may well be the case, it is questionable whether the airstrikes in broad daylight in the middle of a city were proportionate to the coalition’s goals. Woods called the attack of the most brutal strikes Airwars had documented at the time.

Aʿmaq has also claimed that the Ittihad Private University southwest of Manbij was targeted by coalition airstrikes. Satellite imagery of April 2016 indeed confirms that several buildings have been destroyed. The university may well have been used for other purposes, as its buildings are the only large ones along the road leading to Aleppo out of Manbij. The buildings were captured by the Syrian Democratic Force on 6 June 2016.

Airstrikes on oil- and finance-related facilities

The coalition has sometimes described it targets as “assets related to [IS’s] financial base”, a phrase that includes oil-related and finance-related facilities. This has decimated the income of IS within a year, according to IHS researcher Ludovico Carlino, forcing the group to cut salaries too, according to other reports.

The official coalition YouTube channel has published two dozen airstrike videos on oil-related facilities, dubbed Operation Tidal Wave II. Aʿmaq, on the other hand, has only published a handful of airstrike aftermath scenes of oil tankers and markets (8 June 2016 and 20 August 2016 in Mosul, Iraq).

The official coalition YouTube channel has published two dozen airstrike videos on oil-related facilities, dubbed Operation Tidal Wave II. Aʿmaq, on the other hand, has only published a handful of airstrike aftermath scenes of oil tankers and markets (8 June 2016 and 20 August 2016 in Mosul, Iraq).

Airstrikes on financial institutions, however, have been well reported by Aʿmaq, such as an airstrike on the Rafidain bank (18 January 2016) and an unnamed bank (11 January 2016), both in Mosul. The Aʿmaq ground footage of both airstrike aftermaths can be corroborated with official coalition footage of airstrikes on the exact same locations, which the coalition describes as an IS “HQ and financial facility” and “finance distribution center” respectively. An exiled Mosuli, speaking on the condition of anonymity to Hate Speech International, says that his family members in the city insisted the banks were also used by citizens.

Still from A’maq.

The targeted locations mentioned most often by Aʿmaq are “residential neighbourhoods”. Such claims are difficult claims to investigate, as they may well refer to houses where IS fighters have been staying while under surveillance by coalition drones. Nevertheless, there is a risk of civilian casualties and the US CENTCOM has admitted that it has killed civilians in such airstrikes.

Conclusion

It is clear that Aʿmaq adopts the victim narrative in showing the results of coalition airstrikes. In none of its videos is a single militant or any evidence of military equipment on the ground shown. Only civilian casualties attributed to the coalition airstrikes are presented. However, this does not mean that the claims made by Aʿmaq should immediately be discredited: in several incidents the agency’s footage can be corroborated with the coalition’s official airstrike videos. And, in a few cases, the US has even admitted killing civilians. In many other cases, however, it is hard to verify any of Aʿmaq’s claims, since IS has suppressed independent monitors and journalists. While the war between the coalition and IS rages on, so does the information war of who bombed what. And civilians are caught in the crossfire. As a civilian journalist from Mosul, who would like to remain anonymous, tells Hate Speech International: “We’re simply afraid of the IS, but currently just as much for the coalition bombs that are falling everywhere. Many of my friends’ houses have already been blown up. I don’t ask myself whether my house will be gone, but when.” This journalist, whose mother remains in Mosul, dreads what is yet to come. “We’re just as afraid for the coalition’s bombs as we are for Islamic State.”

The author would like to thank Twitter-user @obretix for providing many of the geolocations of the coalition airstrike videos.

Footnote:

- This number is based on information gathered by Airwars. The data is as of 11 December 2016, meaning there were 853 days of the air campaign. It is important to note that an “airstrike” is defined differently by different coalition members, which causes problems for monitoring purposes. For more information, see Airwars’ methodology. ↩

Print Friendly

Print Friendly

[…] https://www.hate-speech.org/the-bombers-and-the-bombed/ […]

[…] To read more about linking Coalition airstrike videos with IS’ videos, please see the article “The Bombers and the Bombed: ” published by Hate Speech International. The approximate locations of these civilian casualties […]

[…] more about linking Coalition airstrike videos with IS’ videos, please see the article “The Bombers and the Bombed: ” published by Hate Speech International. The approximate locations of these civilian […]

[…] https://www.hate-speech.org/the-bombers-and-the-bombed/ […]