Tech-savvy young media producers are boosting the Islamic State’s allure with increasingly competent presentation skills and graphics to enhance the brutal videos that have long been a staple. A video-game ethos is part of the picture.

Øyvind Strømmen

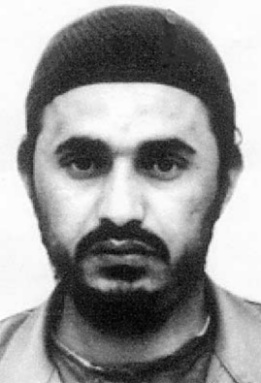

In 2004, a video was released on a jihadist web site hosted in Malaysia. Its introduction was a title screen with a faint, off-white text on a black background. “Sheik Abu Musab al-Zarqawi slaughters an American infidel with his hands and promises Bush more,” the text said. The video goes on to show five masked men in a white room with American freelance radio-tower repairman Nicholas Evan Berg kneeling before them. He’s wearing an orange jumpsuit similar to that worn by the prisoners detained by the Americans at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.

Nick Berg states his name, mentions the names of his parents and siblings, and says he is from West Chester, Pennsylvania.

One of the masked men – believed to be Abu al-Zarqawi himself – reads a lengthy Arabic text:

“How can a free Muslim sleep soundly while Islam is being slaughtered, its honour bleeding and the images of shame in the news of the Satanic abuse of the Muslim men and women in the prison of Abu Ghraib. Where is your zeal and where is the anger for the religion of God? And where is the jealousy over the honour of the Muslims and where is the revenge for the honour of Muslim men and women in the prisons of the Crusaders?

“As for you, scholars of Islam, it is to God that we complain about you. Don’t you see that God has established the evidence against you by the youth of Islam, who have humiliated the greatest power in history, and broken its nose and destroyed its arrogance? Hasn’t the time come for you to learn from them the meaning of reliance on God and to learn from their actions the lessons of sacrifice and forbearance? How long will you remain like the women, knowing no better than to wail, scream and cry? One scholar appeals to the free people of this world, another begs Kofi Annan, a third seeks help from Amr Moussa and a fourth calls for peaceful demonstrations as if they did not hear the words of Allah. ‘O Messenger, rally the believers to fight.’”

He continues by asking if the scholars aren’t fed up with “the jihad of conferences and the battles of sermons”.

The masked man turns his focus onto his enemies, saying: “The dignity of the Muslim men and women in the prison of Abu Ghraib and others will be redeemed by blood and souls. You will see nothing from us except corpse after corpse and casket after casket of those slaughtered in this fashion: ‘So kill the infidels wherever you see them, take them, sanction them, and await them in every place.’”

“God is great”, the man yells, and the five men throw themselves at their prisoner, holding him down, cutting his head off with a knife. The bloodcurdling sounds are no longer in sync with the pixelated, grainy and still very horrible images.

This spring, 11 years later, a video was released by the self-declared Islamic State, a group which originated in Abu al-Zarqawi’s Iraq-based network. The film is called “Healing the Believers’ Chests” and is 22 minutes long. In the upper left corner, an animated version of the group’s black and white flag waves. The video images are sharp, and have been enhanced with effects easily recognized from modern television and – strikingly – video games. The voice of a narrator is accompanied background music: nasheeds, Islamic vocal chants.

The main focus of the video is Jordanian pilot Muath al-Kaseasbeh being burned alive in a metal cage. However, it also has clips of al-Kaseasbeh talking, in the style of an interview with varying camera angles and effects.

These clips are mixed with pictures from hospitals, showing injured children, images obviously intended to leave the viewer with the impression that the victims had been injured in bomb attacks targeting the Islamic State, bomb attacks involving the Jordanian air force. Pictures of dead victims follow. Flames roll across the screen, repeatedly. Then the film shows al-Kaseasbeh, forced to walk through a bombed-out city landscape, surrounded by heavily armed, masked men, with scenes cut together with footage taken by action cameras, footage showing work to rescue bombing victims, seemingly recorded in the same landscape.

The video ends with video game-like pictures declaring that other “Crusade pilots” are wanted.

Both films, of course, show us horrible murders carried out by a militant group of extreme Islamists. However, they also tell us a different story, a story about the development of the IS propaganda apparatus.

“There is a very clear and very significant increase in the quality of production,” says Christopher Anzalone, a researcher at Canada’s McGill University, pointing at both the clarity of much of the footage and the incorporation of soundtracks using nasheed chants, as well as film effects. He also points to a streamlining of narratives, particularly in films of longer length.

“Early Jama’at al-Tawhid and al-Qaeda Iraq films were quite rough in terms of the quality of the footage and, although they also used nasheeds and had narrative structures, they were nowhere near as polished as the current IS films and media materials,” he says.

Anzalone also points to the self-declared Islamic State’s publishing of e-magazines such as the English-language Dabiq, the French-language Dar al-Islam and the Turkish language Konstantiniye. “There has been a notable shift in target audience since the early days under Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. During his tenure as leader, al-Zarqawi did have his group’s media apparatus target external audiences, especially by releasing gruesome hostage execution videos. However, unlike with the IS execution films of today, the early hostage execution videos were narrated in Arabic, rather than English or another Western language. IS now produces many more film and printed materials in the languages of their target audiences, for example propaganda and messaging materials in Turkish for Turks, Uyghur for Uyghurs, English for English speakers, Hausa for Hausa speakers, Russian for Russians and Russian speakers, and so on.”

“A good deal of the technical advances are no doubt because of the increasing quality of technology; laptops, design program suites, film and sound editing tools, graphics, et cetera,” Anzalone points out. “However, there has been a clear evolution and increasingly streamlined advance in the presentation of increasingly pinpointed narratives to a greater number of target audiences since 2009–2010, and even more rapid advances since 2013.”

The founder of IS’ predecessor group Tawhid wal-Jihad, Abu al-Zarqawi – actually named Ahmad Fadhil Nazzal al-Khalayah – was also concerned with communication. In younger years, Abu al-Zarqawi was a petty criminal in his Jordanian hometown of Zarqa. Then he turned to radical Islamism, and left for Afghanistan. As one of the so-called ‘Afghan Arabs’, he took part in the fight against the Soviet occupation of the country in the 1980s.

At first, he was not a fighter. Instead, the young Jordanian worked as a reporter for a small magazine named al-Bunyan al-Marsous, or ‘the Strong Wall’. The magazine was published in the Pakistani city of Peshawar and brought news in both Urdu and Arabic, with the Islamist fighters in Afghanistan as their target audience.

It was before the days of the World Wide Web, and the magazine was distributed as a traditional print publication. To the Islamic State, however, the Internet is crucial. Its propaganda is spread through social media platforms, video sites and electronic magazines. For a while, the English-language version was even accessible through the Internet bookstore Amazon.

IS media operators – most of them probably fairly young – are more tech savvy than their predecessors, use more modern imagery, and their magazines feature better graphic design; simple, yet somewhat sleek.

“They come from the YouTube and social media generation, so to speak,” Anzalone says. “Their videos frequently use video game-like effects, particularly in the form of ‘first person’ shots, using technology such as GoPro action cameras. IS media production teams also have a penchant for using slow motion replays, often two, three and more ties, of particular ‘scenes’, so to speak, such as explosions, the charge of fighters or the firing of various weapons. Although they are not in every IS film, the majority of which are fairly short, these types of effects are a cornerstone of their style of media production.”

“IS media have many characteristics of modern popular culture,” says Pieter Nanninga, a researcher at the University of Groningen, in the Netherlands. “Nasheeds are very important. The videos also show resemblances with Western films, documentaries and video games. A vivid example of the latter is the use of action cameras during battles, which give the impression of a first-person-shooter game.”

Noting that the group manages to attract young people in different parts of the world, Nanninga adds: “This ‘embedded-ness’ in modern popular culture, or youth culture, shows that IS is a modern movement, a product of our time. They offer a clear worldview, a strong identity and a feeling that you can be important as part of a powerful movement which, in their view, defends the honour of Islam and Muslims against oppression and humiliation by the West and their ‘puppets’ in the Middle East.”

Journalist Mah-Rukh Ali, a news anchor at Norway’s main commercial television channel, TV2, recently published the book Trusselen frå IS. Terror, propaganda og ideologi (The IS threat: Terror, propaganda and ideology). In her opinion, both journalists and researchers often make IS propaganda sound better than it is.

“I am not especially fond of how some of the IS propaganda is described,” she says. “It is portrayed as brilliant, sophisticated or professional. In my opinion, we describe them as more professional than they are, partly because we have problems understanding the movement at all.”

Like Anzalone, Mah-Rukh Ali points out how technology helps IS: “This is a movement of our time, and they make use of what is accessible to them. When we compare to al-Qaeda material from the past, we are making a comparison with phenomenon of the 1990s and the 2000s.”

Ali sees the IS media strategy as simple. “The areas they control have been isolated from the outside world, making us dependent on their propaganda,” she notes. “Editorial teams in the Western world often defend themselves by saying that they are not spreading propaganda but only showing reality. However, we allow ourselves be used by IS whenever we use their material.”

Ali believes experts and opinion makers who portray IS propaganda as being sophisticated should think again: “They build a kind of fascination with the IS. But, attaching a microphone to a victim really isn’t very difficult.”

She sees “shock effect” as an important part of IS propaganda.

“This is true for the beheading videos, which are nothing new – Mexican drug cartels have long done the same,” Ali says. “It is also true for the video of the Jordanian pilot being burned alive, and for the destruction of cultural heritage sites, for instance in Palmyra. It is a way of getting attention in international – in Western – media.”

The IS media strategy is not just about shock effect, however. “To understand IS, it is important to note that their media is not all about violence and bloodshed,” Nanninga says. He estimates that a bit more than half of the videos show violence in some form, such as battle reports and executions. Other videos show different aspects of the self-declared state. “State building is the most important theme of IS media,” he says. “Many executions are also presented within this context, as establishment of law. The Islamic State presents itself as a state-in-the-making, where Muslims can live a good and honourable life.”

As a recent example, he points to a series of propaganda videos on refugees, in which the Islamic State warns Syrians not to seek refuge in Europe but rather to remain or seek out their self-declared caliphate.

State or nation building is a central point in Islamic State propaganda, as two recent examples attest. In mid-November, a media unit called al-Furat released a video called “En Mujahids Eid”, Swedish for “The Eid of a Mujahideen”. The film focuses on the celebration of Eid, and while it includes jokes about butchering not only sheep but also disbelievers, the focus is on the end of Ramadan celebration, on community, on happy children and on handing out food to poor people.

The Scandinavian film also features spoken Swedish, with at least eight people with connections to Sweden pictured. Seven of the eight are from the southern Sweden city of Gothenburg. The message? Muslims should come to the self-declared Islamic State, rather than living their lives amongst the kuffar, the disbelievers. It is a message often repeated in IS propaganda.

In late November another video summarizing several central points in IS propaganda was launched, in English, Arabic and several other languages. Titled “No Respite”, the video has a film-trailer style voice and some effects that bring video games to mind. The booming voiceover with an American accent brags about the size of the self-declared caliphate and its system of rule, mocks America, attacks nationalism, portrays the Islamic State as anti-racist, and says that it is counting the banners of its enemies. “Bring it on,” the voiceover says, promising that the “flames of war will burn you on the hills of Dabiq”.

State building is a theme often seen in IS propaganda. Here: propaganda focusing on the introduction of the gold dinar.

Dabiq is the name of a small town in north-western Syria, just a few kilometres from the Turkish border. Once, a deciding battle between the Ottomans and the Mamluks took place there. In Islamic eschatology, the town is also mentioned as the place where an important battle between “the Romans” and an “army consisting of the best of the people of the Earth” is will take place before Judgment Day.

“The Islamic State produces different kinds of media, such as videos, audio messages and magazines,” says Nanninga. He points out that they produce much more material than earlier jihadist organizations. “Their most important media branch is al-Furqān Media, which produces the most important videos. Al-Hayat is another important one, which publishes mostly in English and focuses on an international and Western audience. This outlet also produces Dabiq magazine.

The Islamic State expects Dabiq to be the site of the final battle between it and “the Coalition of the Devil”. The use of Dabiq in the video “No Respite” and as the name of the organization’s most important electronic magazine is hardly accidental. It underscores the Islamic State’s belief that the apocalypse is approaching.

“The magazine puts a heavy emphasis on connecting the politics and ideology of the Islamic State with Islam,” says the Norwegian historian Øystein Sørensen, who has written extensively on totalitarian ideologies. “Obviously, they know that their interpretation of Islam is controversial, and their focus on defending their position through the use of quotes from the Koran and from hadiths comes under scrutiny.”

In Sørensen’s opinion, IS propaganda and that of other totalitarian movements have clear similarities. However, he sees one important difference: “They promote their own brutality. They brag about it, and describe it in detail, in text and imagery. You will not find the same if you study the propaganda of Nazi Germany, Stalin’s Soviet Union or the China of Mao. There, brutality was directly or indirectly denied and covered up.”

“Execution videos and the destruction of cultural heritage sites are ways for IS to get attention in international media,” explains Ali, the Norwegian TV anchor. “Dabiq, on the other hand, has language filled with religious rhetoric. The Islamic State is trying to take control of Islamic concepts, and attempts to have a defining role in deciding what Islam is. They try to give their actions a religious fundament.”

“The magazine successfully accomplishes a number of things for the Islamic State,” says Anzalone. “First, it creates a lot of buzz in the international news media and, more broadly, amongst the ‘cyber commentariat’ – from independent bloggers to analysts. This buzz furthers the IS’s image of power, sophistication and threat, which the group’s leaders seek to create and feed. Secondly, it serves as a form of messaging and narrative framing, aimed at certain target audiences.”

Anzalone points out how key Dabiq articles are then translated into other languages, including German, Arabic, Russian and Indonesian, either officially by an IS media organ or by other publications and individuals supporting the group. “Many of the articles in the French-language IS publication Dar al-Islam were first published in English, for instance,” he says.

Targeting the Arab street. While the importance of Dabiq should not be ignored or underestimated, Anzalone underscores that the vast majority of IS media operations are published in Arabic rather than English or other European languages. “The da’wa (missionary) pamphlets and booklets published by the group are almost entirely in Arabic, and very few of them have been translated officially,” Anzalone says. “The vast majority of IS films are also in Arabic, though many are later translated.”

In addition to films, magazines and pamphlets, IS actively spreads photographs. Here, production is carried out on a regional level, through the media offices of the so-called wilayats of the Islamic State. “Thousands of official photographs are released online,” Anzalone says. He archives photographs spread by the group, and when HSI spoke to him in October he had assembled more than 27,000 since 2014. Furthermore, the Islamic State has started producing its own original nasheeds for use in propaganda, launching “music videos” in Arabic, but also in other languages – including Uyghur, German, French and Turkish.

Central to all this propaganda work, however, is social media. “It is the primary means through which the group’s various media organs initially release new media materials,” Anzalone says. “In this, the Islamic State has been at the forefront of jihadi media. Previously, most jihadi groups relied on a set of jihadi Internet web forums for their media releases. They would maintain relationships with the administrators of these forums in order to plan releases. Today, although some of the forums still exist, they are no longer as central. Jihadi groups have moved on to social media sites, such as Twitter and Facebook.”

Providers have increasingly clamped down on pro-IS and IS-affiliated accounts, but IS supporters and media operatives have been countering this by creating a steady stream of new accounts. In short, social media function as a springboard, allowing the IS to get its message out. It may not be sophisticated, but it is effective.

Parts of this article were published in the Norwegian weekly newspaper Morgenbladet.

Print Friendly

Print Friendly

[…] relevant reading: – ISIS and the Big Three, by J.M. Berger – The IS Media Jihad, by Øyvind […]