ANALYSIS: Since the beginning of the Syrian uprising in March 2011, debates have been going on about the role of urban people versus the role of rural people in igniting and leading the uprising. Tribal identity still plays a role in the Syrian civil war, and is used by the different parties involved.

Haian Dukhan

Since the beginning of the Syrian uprising in March 2011, debates have been going on about the role of urban people versus the role of rural people in igniting and leading the uprising. The Syrian uprising seems to have been the first in the Arab world that was sparked in rural areas or in the outskirts of cities inhabited mostly by rural people. Affluent parts of the cities (including Aleppo, Damascus and Homs) did not play a major role in the uprising. The Syrian uprising appeared to be a revolt of the “periphery against centre”, unlike the protest movements in Tunisia and Egypt that were led by the urban classes of the capitals and major cities. Rural Syria, where the protest movement was most prevalent, is home to the majority of the country’s Bedouin tribes. Moreover, the majority of people who live in the outskirts of big cities belong to tribes and preserve their tribal customs.

When the protests began, tribalism played a major role in the restive areas of Syria to mobilize youth in the protest movement against the regime. As peaceful protests transformed into violent confrontation, some tribesmen resorted to armed self-defence. As a result, concerted, large-scale campaigns were initiated by both the regime and the opposition to win over the tribes and use them militarily and politically in the battle over Syria. On first glance, it may appear that some tribes allied with the regime and others with the opposition, but the divisions are in fact less clear. Many tribes were split, with some clans supportive of the regime and some opposing it. With the passage of time, the Syrian uprising turned into an armed conflict that attracted more players than the regime and the Free Syrian Army. Islamist groups and the Kurds became prominent actors in the conflict and they both tried to manipulate the tribes to serve their interests.

This paper will argue that tribal identity was (and is still) used by the Syrian regime, the opposition, the Kurds, the Islamists and international powers like Jordan, Iran, Turkey and the US to mobilize and direct the armed activities of tribesmen. Such self-interested manoeuvring in the Syrian conflict has led to fragmentation of the tribes into competing clans 1 that have been instrumentalized in large part by outsiders.

Geography and population

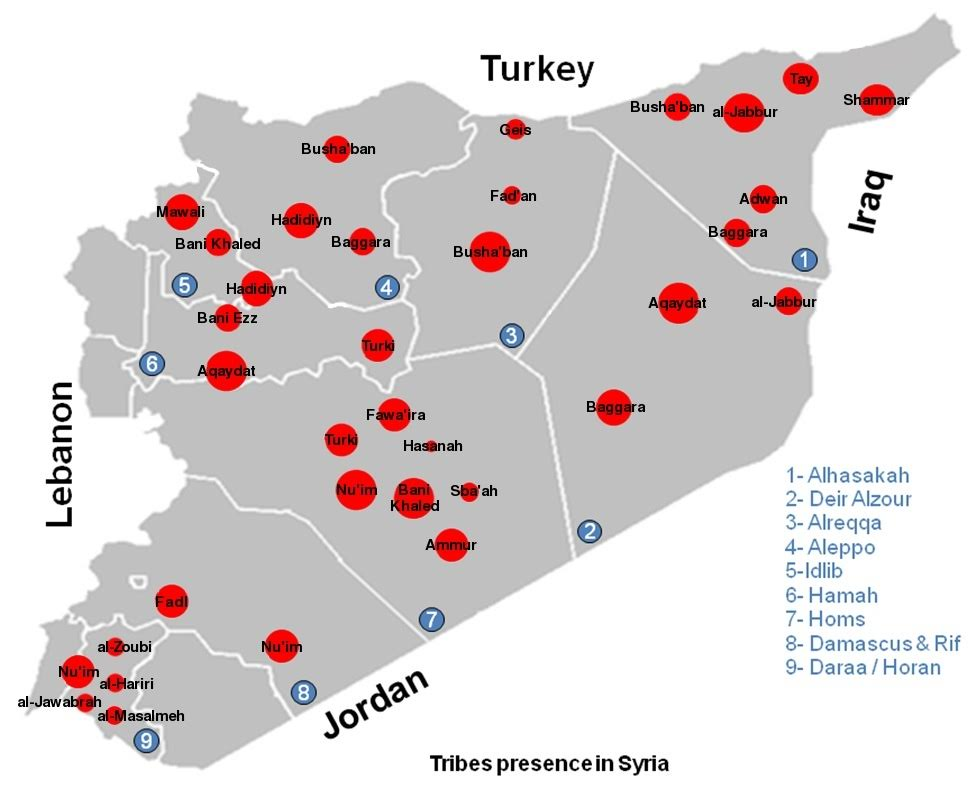

Bedouin tribes in Syria inhabit three geographical regions. These three regions include: al-Badia (“the Steppe”), Al-Jazira (“Island”) and Hauran. These three regions are called the tribal regions and have been the scene of constant political struggle between the Bedouin tribes and the central state. See the above map for the names of key tribes and their distribution in Syria. Bedouin tribes constitute 20% of the Syrian population.

Fragmentation in the Civil War

In general, Bedouin tribes do not have a unified military council to lead and coordinate their armed activities. They are fragmented and manipulated by the regime, the Islamists, the Kurds and other regional powers like Iran, Jordan and Turkey. Many Bedouin youth who took part in the protests decided to carry arms against the regime after the death or torture of a relative at the hands of the Syrian regime security forces.2

The Syrian army had large number of Bedouins serving in its ranks. Many started defecting from the national army to join the Free Syrian Army. Many army officers with tribal background started to rise in the Free Syrian Army, such as Maher al-Nuimi of the Nuim tribe and Abdul Jabbar Akidid of the Egidate tribe. Some Bedouin army officers established tribal militias using the names of their tribes, though their military activities were not managed or coordinated by their tribal Sheikhs. In fact, the Sheikhs often opposed forming such militias. For example, some members of the Bani Khaled tribe formed a battalion known as the Shield Brigade to fight under the umbrella of the Syrian army in Homs3. Members of the al-Mawali tribe set up a tribal militia known as al-Mawali brigade fighting under the banner of the Free Syrian Army in Idlib4. On the other hand, the Syrian regime asked its loyal Sheikhs to set up militias and mobilize their youth to fight with the regime. For example, Sheikh Mohammad al-Fares of the Tay tribe and a member of the Syrian parliament established a tribal militia in al-Hassakeh as part of a national defence force that belongs to the Syrian regime. In Idlib, Sheikh Ahmad Darwish of the Bani Ezz tribe and a member of the Syrian Parliament set up another pro-regime militia of his tribesmen. When Jabhat al-Nusra took over his village, he was executed.5

In some cases, there have been two conflicting tribal militias from the same tribe: one supporting the regime and one fighting against it. Tribal youth, for example, may form a rebel militia and give it their tribal name while their traditional leader sets up another militia with the same name but fighting with the regime. Some members of the Hadidiyin tribe are fighting alongside the opposition near Aleppo6, and other members are fighting with the regime as part of a militia set up by Fahad Jasem al-Frej, the Minister of Defence who belongs to the Hadidiyin tribe near Idlib. This pro-regime Hadidiyin militia in Idlib have helped supply food and aid to besieged forces of the Syrian regime. After capturing their areas in Idlib, Jabhat al-Nusra managed to capture Sheikh Nayef al-Saleh of the Hadidiyin and beheaded him in public for trying to help Syrian regime soldiers besieged at Abu-Dohor airport.7 Regime-friendly media mourned the Sheikh, depicting him as a patriotic hero. Some Baggara tribesmen are reportedly fighting with the Syrian regime against the opposition in Aleppo while other Baggara tribesmen are fighting against the regime in Deir Ezzor.

By the end of 2012, it became clear that the Syrian regime was not going to be defeated soon, thanks to diplomatic and military support from Iran and Russia. The uprising stated to turn into a civil war. The Free Syrian Army began fragmenting into different militias. When Syrian regime forces withdrew from most rural areas in the north-eastern part of the country, tribes fragmented into clans and there was competition among the clans to gain war spoils.8 The most important of these were oil and gas fields, which were taken over by different clans in the countryside of Deir Ezzor and Hassakeh. These fields were then run and managed by clan fighters who would distribute the benefits to clan members and use the surplus to buy more arms and ammunition to enable them to protect the fields. The new focus of many tribal militias was to gain as much as possible from the oil fields and make alliances with other fighting groups (ISIS, Jabhat al-Nusra or even the Syrian regime) in order to survive.

The rise of the Islamic State and its conflict with Jabhat al-Nusra in eastern Syria in 2014 led to a devastating inter-tribal war that lasted many months. The clans of the Egidate tribe split between Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS. The Al-Bakir clan fought with ISIS while the al-Bukamel and Sheitat clans sided with Jabhat al-Nusra against ISIS.9 The result was the defeat of Jabhat al-Nusra and its allies, who have been displaced from their villages and massacred by ISIS fighters.10 The Syrian regime played on the grievances of the Sheitat clan by offering refuge and shelter to clan members who had managed to survive. This clan then set up a tribal militia known as Ussud al-Sharqiya (Lions of the East) with an estimated 700 to 900 fighters to fight with the Syrian regime in the regime’s last strongholds of Deir Ezzor11. Tribal militias from the Tay and Sharabyen tribes were set up in al-Hassakeh governorate, where they received training from Iranian troops. They are currently fighting with the Syrian regime against ISIS in their region.

In addition to fighting with the regime in al-Hassakeh, the Sharabyen tribe is also assisting the Kurds alongside the Shammar tribes in their battles against ISIS in al-Hassakeh governorate. Turkey, wary of growing Kurdish power in Syria and the alliances that the YPG12 has begun to weave with some Bedouin tribes in the region, has started to play the tribal card itself. Exploiting thousands of tribal refugees displaced to Turkey as a result of ethnic cleansing by the YPG (according to Amnesty International13), the Turkish government has sponsored the establishment of what is called the “Eastern Tribes Army” with the aim of fighting ISIS and resisting YPG attempts to take over the “Arab tribal territories”, according to a statement by tribal leaders who met to establish this army.14 It is still not clear yet whether this army will be a pivotal force on the ground or whether the announcement of its establishment is just part of Turkey’s media war against the YPG.

ISIS has tried hard to recruit youth from the tribes. The organization released many videos of Baggara, Egidate, Jabbour and Bu Sha’an tribal leaders pledging alliance to the so-called caliph. ISIS understands that tribal structure has changed over time and that there is a young generation that rejects the traditional chiefdom. Therefore, ISIS co-opts young tribal leaders by offering to share oil and smuggling revenues with them and promising them positions of authority. For example, ISIS appointed Ali al-Sahou, 28, as the head of its security office in Raqqa. He works on recruiting young people from his tribe (Bu Sha’ban) and other tribes in Raqqa to join ISIS.15

On the southern front, Jordan has played a major role in coordinating the activities of the rebels. Trying to limit the growing influence of Jabhart al-Nusra and ISIS in the southern part of Syria, Jordan supported the establishment “the army of the free tribes”, composed of 3,000 fighters from different tribes.16 This announcement took place after calls by Jordan’s King Abdullah to train and arm the Syrian tribes to fight against ISIS and other extremist Islamist groups.17 The United States and its allies have recruited fighters from among Syrian refugees belonging to the tribes and living in Jordan and Turkey, in order to create groups that can fight ISIS on the ground. This has resulted in “the New Syrian Army”, composed of members of tribes from eastern Syria but living in Jordan, who were used in a recent military operation against ISIS in the town of Al Bukamal.18 The second group is Jabhat Thuwar al-Raqqa, which is composed of tribes in the northern Raqqa countryside. The aim of training and funding this tribal militia is to assist the Kurds in their attempt to liberate Raqqa from ISIS.19

Conclusion

The uprising in Syria started in the periphery and not the centre. From the early days of the uprising, tribal kinship provided support networks for the protesters who relied on their relatives for help and protection from the regime’s suppression. Long years of clientelism between the regime and the Sheikhs helped the regime survive and severely divided the tribes as the Sheikhs recruited certain members to fight with the regime. Other members of the same tribes in many cases formed tribal militias that joined the Free Syrian Army. They received funding and support from their relatives in the Arab Gulf states, Iraq and Jordan who wanted to use the tribes to advance their interests and topple Assad’s regime. Iran, which is supportive of the Syrian regime, created its own tribal networks in Syria and used them to fight the Arab Gulf networks. The emergence of ISIS in Syria made the US and its allies look to the tribes for support in their campaign against the terrorist group. As the conflict in Syria has escalated, tribes have fragmented and turned into pieces on a chessboard, moved around by international and regional powers. Whether the Syrian regime falls or stays in power, international players will need the cooperation of the tribes to rebuild Syria’s fractured polity.

Footnotes

- The tribe in Syria; as in the rest of the Arab world, is divided into smaller parallel sections – asha’ir (clans) and afkhad (lineages). ↩

- Haian Dukhan, “Tribes and Tribalism in the Syrian Uprising”, Syria Studies Journal 6 (2014): 9. ↩

- أموي مباشر. “Bani Khaled Shield Brigade”. YouTube video, 0:59. 27 January 2013. ↩

- Shamee Forever. “Annoucing establishing al-Mawali tribe brigade”. YouTube video, 0:27. 3 February 2012. ↩

- Sarmad Khalil, “The Destiny of a Parliament Member is unknown after Jabhat al-Nusra took over his village”, all4Syria, 12 May 2015, accessed 18 July 2016. ↩

- Dawn Chatty, “Syria’s Bedouin Enter the Fray, How Tribes Could Keep Syria Together”, Foreign Affairs Magazine, 13 November 2013, accessed 18 July 2016 ↩

- Zayd al-Mahmoud, “Jabhat al-Nusra executes Sheikh al-Haddidien”, all4Syria, 3 June 2015, accessed 18 July 2016. ↩

- Isam al Khafaji, “De-Urbanising the Syrian Revolt”, Arab Reform Initiative, March 2016, accessed 18 July 2016. ↩

- Souriatna, “ISIS and the tribes in the Syrian Jazirah”, Center For Environment and Social Development, 2 August 2014, accessed 16 July 2017. ↩

- Alhayat, “ISIS defeats Jabhat al-Nusra in Deir Ezzor and controls its oil”, Alhayat, 4 July 2014, accessed July 18, 2016. ↩

- Middle East Eye, “Who are the pro-Assad militias in Syria?”, 25 September 2015, accessed 18 July 2016. ↩

- The YPG is the military wing of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the main Kurdish political party in Syria. ↩

- Richard Spencer, “Syrian Kurds accused of ethnic cleansing and killing opponents”, Telegraph, 18 May 2016, accessed 18 July 2016. ↩

- Turkpress, “Establishing the Army of Eastern Tribes to confront the federalism of the Democratic Union Party in Syria“, Turkpress, 18 March 2016, accessed 18 July 2016. ↩

- Maamoun al-Sayed, “Who is the head of the security office of ISIS and why does he enjoy unlimited authorities“, all4Syria, 21 January 2015, accessed 18 July 2016. ↩

- Orient News, “What is the Army of Tribes and why is Jordan supporting it?”, YouTube video, 15:11. 2 December 2015. ↩

- Khetam Malkawi, “Jordan to extend help to Syrian, Iraqi tribes ‘which ask for it’“, Jordan Times, June 20, 2015, accessed July 18, 2016. ↩

- Seyed Abd al Majid Zavari, “What’s Behind US Air Force Abandoning New Syrian Army on the Battlefield”, sputniknews, 8 July 2016, accessed 18 July 2016. ↩

- Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “Liwa Thuwar al-Raqqa: History, Analysis & Interview”, Middle East Forum, 14 September 2015, accessed 18 July 2016. ↩

Print Friendly

Print Friendly

[…] manoeuvring in the Syrian conflict has led to fragmentation of the tribes into competing clans 1 that have been instrumentalized in large part by […]