ANALYSIS: The European Elections were not the watershed victory for the far right that the media makes them out to be.

Cas Mudde

Sympathizers of Jimmie Åkesson, the Sweden Democrats party leader, as he spoke at Norrmalmstorg in Stockholm on 24 May 2014. (Photo: Frankie Fouganthin, under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0)

Media reports on far-right gains in the 2014 European elections called it a “sweep” and an “earthquake”. In the words of The Financial Times: “Eurosceptics storm Brussels”. None of these headlines are unexpected (I predicted “Far right marches on Brussels”) and these were indeed landmark elections in some respects. Yet the alarmist and somewhat sensationalist reporting is often devoid of nuance and much-needed historical context. Political scientists have conducted extensive research on far-right parties in Europe, which helps put some of the popular conclusions and explanations to the test.

I have summarized the results of the far right elsewhere. There were indeed two far-right firsts in the 2014 elections: (1) two far-right parties, the Danish People’s Party (DFP) and the French National Front (FN), became the biggest party in a nationwide election in an EU country – although this has been the case in Switzerland (since 1999); (2) more or less openly neo-Nazi parties – the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) and the Greek Golden Dawn (XA) – for the first time entered the European Parliament, although the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement (MSI) and several of its radical splits have been represented in almost every EP since popular election was introduced in 1979.

The table below shows that far-right parties significantly increased their representation in the EP, gaining a record 52 MEPs, up by 15 seats since the 2009 election. The precise gains depend a bit on issues of conceptualization and categorization. Notably, there are a couple of important borderline cases, i.e. parties that some scholars consider to be far-right and others do not. Of these, some have far-right factions, but are not overall far-right parties – this is the case with the Finns Party (PS) and the Latvian National Alliance (NA). Other parties employ a far-right discourse, particularly around election time, but do not have a far-right core ideology – I believe this to be the case, for example, with Fidesz-Hungarian Civic Coalition and the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP). Finally, some parties are simply quite unknown, at least to scholars outside of the particular country; for example, I know too little about the ideological core of the fairly idiosyncratic Bulgarians Without Censorship (BWC) and Polish Congress of the New Right (KPN) to make a solid judgment.

All this notwithstanding, it is clear that Europe as a whole wasn’t hit by a far-right earthquake. As has been the case since the emergence of the so-called “third wave” of far-right parties in the early 1980s, the successes of individual parties differed significantly across the continent. For example, only 10 of the 28 member states (i.e. 36 percent) elected far right MEPs. And while there was a total increase of 15 far-right MEPs compared to the 2009 election, the FN alone gained an extra 21 seats! In many ways, the success of the European far right is really the success of the FN (and to a lesser extent the DF). Overall, far-right parties gained additional seats in just six countries, while they lost seats in seven others. Most striking, while two “new” far-right parties entered the EP for the first time (XA and Sweden Democrats), five lost their representation in Brussels – Ataka in Bulgaria, the British National Party in the UK, the Popular Orthodox Rally in Greece, the Greater Romania Party in Romania and the Slovak National Party in Slovakia.

All this notwithstanding, it is clear that Europe as a whole wasn’t hit by a far-right earthquake. As has been the case since the emergence of the so-called “third wave” of far-right parties in the early 1980s, the successes of individual parties differed significantly across the continent. For example, only 10 of the 28 member states (i.e. 36 percent) elected far right MEPs. And while there was a total increase of 15 far-right MEPs compared to the 2009 election, the FN alone gained an extra 21 seats! In many ways, the success of the European far right is really the success of the FN (and to a lesser extent the DF). Overall, far-right parties gained additional seats in just six countries, while they lost seats in seven others. Most striking, while two “new” far-right parties entered the EP for the first time (XA and Sweden Democrats), five lost their representation in Brussels – Ataka in Bulgaria, the British National Party in the UK, the Popular Orthodox Rally in Greece, the Greater Romania Party in Romania and the Slovak National Party in Slovakia.

As is so often the case, the differences within the far right tell us much more about the reasons for their electoral success (and failure). I will focus on three particular factors: (1) the role of the economy; (2) regional characteristics; and (3) the importance of “rebranding.” All of these factors have come up regularly in media reports of far-right success since the early 1980s, and have been addressed in much academic research (for an overview see my book: “Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe“).

The idea that far-right parties profit from economic crisis has been around since Hitler’s rise to power in Weimar Germany in the early 1930s. As I have argued in more detail elsewhere, the thesis does not hold up under empirical scrutiny. This was confirmed in the 2014 European elections, where only one of the ‘bailed out’ countries returned far-right MEPs (Greece). Interestingly, in four of the five bailout countries the far left did gain overall (Portugal being the exception).

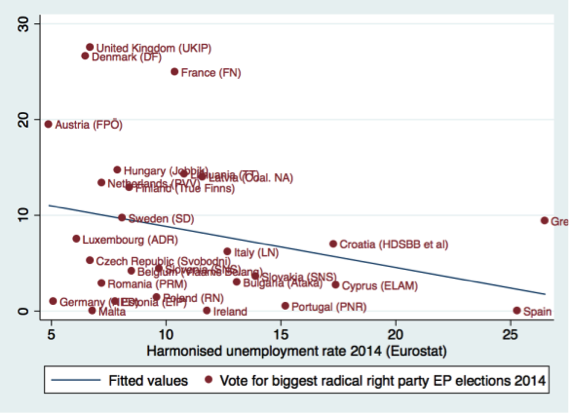

More generally, in a quick scatter plot (see below), Alexandre Afonso found “a small to moderate negative correlation” between the level of unemployment and the score of far-right parties in a country (though he used a somewhat broader categorization). In fact, the best electoral results of far-right parties were almost exclusively in countries that were, compared to other E.U. countries, little to moderately affected by the crisis: Austria, Denmark, France, Netherlands and Sweden. The only exception to this rule is Hungary, which has been hard hit by the crisis and had the fourth-highest score for a far-right party.

These results are fairly consistent with the rise of far-right parties in Western Europe since the mid-1980s. Not only did the parties emerge in a period of relative affluence, but they tended to perform best in the richer countries (e.g. Denmark, Switzerland) and regions (e.g. Flanders, Northern Italy) in western Europe. The explanation is that contemporary far-right parties, just like Green parties, are mainly a post-materialist phenomenon, which emphasize socio-cultural issues and are involved in identity politics. Economic issues are secondary for both the parties and their voters. Hence, in terms of crisis, when socio-economic issues push socio-cultural issues to the sidelines, far right parties have little to offer and (some of) their voters will either not vote or look for a party with a more pronounced economic profile (and competence).

This is not to say that the Euro Crisis doesn’t play a role in the electoral success of far-right parties. They can frame the crisis in socio-cultural terms, i.e. appealing to the threat of the EU to their national identity, particularly in those countries least affected by the crisis. Consequently, rather than having to provide potentially complex socio-economic alternatives, far-right parties can link the E.U. bailout policies to their core ideological features: nativism, authoritarianism and populism. Playing to nativist stereotypes, they argue that elitist and wasteful Eurocrats force “us” to pay money to the corrupt and lazy “them.” On top of that, they present the image of “our nation” being threatened by criminal immigrants from southern and eastern Europe

As Lee Savage laid out here, central and eastern Europe were largely ignored in media accounts of the European elections and do not fit the earthquake narrative. The far right lost representation entirely in three countries, and in the one country where it maintained a significant presence, the vote shares were slightly below those from 2009.

This is quite remarkable, as post-communist Europe has long been treated as a nationalist hotbed ripe for extremist political forces. While earlier studies significantly nuanced this stereotypical view, particularly with regard to far-right organizations, the 2014 European election results should lead to some soul searching. Ostensibly eastern Europe provides a fertile breeding ground for far-right parties, including: broadly shared prejudices towards minorities, high levels of corruption, a large reservoir of so-called “losers of the transition”, etc. Nevertheless, support for these parties has not materialized.

One explanation for the abysmal performance of radical right parties in eastern Europe is that mainstream right-wing parties in the region leave little space for the far right, given their authoritarian, nativist and populist discourse. This is often mentioned with regard to the quick demise of the far-right League of Polish Families (LPR), as a consequence of the right-wing turn of the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) party.

However, in Hungary the at least equally authoritarian and nationalist mainstream right-wing party Fidesz is confronted with the only strong far-right party in the region, Jobbik. In this context, commentators argue that the relationship is actually the other way around, in that a very right-wing mainstream party legitimizes the far right, which helps them gain support.

But this wouldn’t explain the Poland case. Within a western European context I have called this the “Chirac-Thatcher debate” and suggested that actually, both arguments can be true, but there is an intervening variable: issue ownership. If a far-right party is able to “own” far-right issues like crime, corruption and “ethnic minorities”, it will profit from the rise in issue salience as a consequence of the discourse of the mainstream (right-wing) party. If not, the mainstream (right-wing) party can grab the unclaimed issue and own it, leaving little space for the far right. What sets eastern Europe apart from western Europe is the lack of institutionalized parties and a stable party system, which also means that few parties, mainstream or far right, have and can hold onto issue ownership.

The volatility of the eastern European party systems could also account for the lack of far-right success in another way. In many western European party systems, far-right parties are among the few outsider parties that can mobilize against a “cartel” of established parties. On top of that, they profit from a heightened sensitivity to the far right, which makes them the specific target of elite campaigns. This all perfectly fits their populist propaganda of “one against all and all against one”. In eastern Europe the political opportunity structure is much less favorable. First, there are few stable party cartels because of the high level of elite and mass volatility. Second, every election brings a host of new challenger parties. Third, the sensitivity toward the far right is much less pronounced, which makes them stand out less from the pack of challenger parties.

Finally, a lot of media have explained the success of particularly the FN by arguing that Marine Le Pen has rebranded the party, making it more moderate and professional. It is the “far right 2.0” that succeeds where the (presumably) “far right 1.0″ of anti-Semitic leaders and racist skinhead supporters failed.

The thesis of a new radical right has been used at least three times since the early 1980s and, whether we like it or not, the new new radical right is actually quite old. Whereas Marine’s father Jean-Marie Le Pen has become a caricature of himself in recent years, 25 years ago he was considered one of the most charismatic political leaders in Europe. In fact, his unscripted speeches were so popular that thousands of people would pay to hear him speak – at a time when most politicians had to bribe their audiences with free drinks, food and gifts.

Similarly, current FPÖ leader Heinz-Christian Strache, or HC in the cult of personality in the party, is heralded as part of “a new generation of leaders” that look much more respectable than the “historic leaders” of the 1980s and 1990s. But journalists wrote exactly the same about his predecessor, Jörg Haider, for whom the term “designer fascist” was invented.

In short, while the European elections did bring some new developments in terms of far-right successes, most of the success came from well-established far-right parties that have been operating in a new style for decades. So, rather than reinventing the wheel over and over again, commentators, academic and non-academic, should first consult the wealth of studies on far-right parties, which seems quite capable of explaining most of what is going on today.

This article, written by Cas Mudde – an assistant professor in the School for Public and International Policy at the University of Georgia and author of “Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe” – was first published on the Monkey Cage. It has been republished here with the kind permission of Mudde and the Monkey Cage.

Print Friendly

Print Friendly

No comments yet.