IN DEPTH: The Facebook profiles of online jihadists reveal a struggle to balance the lures of Western entertainment and technology with strict Islamic identity.

Lars Akerhaug

Typically, Facebook is a place for uploading pictures of your kids or updates on that trip to Paris. But Facebook is growing in importance, day by day, as a recruiting pool and online laboratory for jihadist thought. Facebook is a place where an aspiring fighter of holy war can shape and refine his image. Sitting in front of a computer, he can leap into the world of virtual jihad. The battle to achieve a khilafah – an Islamic super state as envisioned by Osama bin Laden’s supporters – is fought not only on battlegrounds like Syria and Afghanistan. It is a virtual struggle, fought daily from laptop computers and smartphones all over the Western world.

Ideological supporters of al-Qaeda and similar groups use Facebook in different ways, of course. Typically, a semi-anonymous profile is used, with a false nom de guerre. Yet the virtual jihadist is easily recognizable to those who are already acquainted with him. Completely anonymous profiles are in fact rather uncommon on the social networking website, and some Facebook jihadists do not bother hiding their identity at all.

The jihadist rallying symbol is the black flag with white script reading “la ilaha illa Allah”, meaning “There is no god but God”. The flag is sometimes also presented with the creed in black script on a white background. Both variations are typical for jihadists presenting themselves on Facebook.

Let us take the example of “Abu Baraa”, a person apparently residing in the UK and aligned with the movement of the Islamist cleric Anjem Choudary. In his Facebook profile picture, Abu Baraa appears to be giving a lecture or a speech with the black Islamic flag draped in the background against a wall. While he does not use his full name on Facebook, both his acquaintances and MI6 must know who he is. This may be the same Abu Baraa who in 2012 was listed as a spokesperson for “Sharia4India”, residing in the UK.

By choosing Abu Baraa as his nom d’guerre this activist also tries to say something about who he is and what image he wants to portray. “Abu Baraa” is an Arabic name meaning “the father of an innocent” or “the father of innocence”. But that meaning is uncertain. “Baraa” is part of the Arabic phrase “Al-wala’ wal-bara'”, which carries an essential meaning for the crowd of supporters around Choudary. The sentence could be translated to “Command the good and forbid the evil.” It is an essential part of the ideological universe that Choudary and his supporters operate in and serves as a justification for their political activism, for they see it as their Islamic duty to attempt to sway the society they live in towards Islamic ideals and ultimately towards the creation of an Islamic state.

The symbolism of the black and white flag is quite often mixed with gun-toting imagery. An example is “Idris Bukara”. His profile picture features the flag bearing the Islamic creed, and below it a picture of a gun – apparently an AK47, popularly called a Kalashnikov. “Idris” appears to be a young man of African heritage. The images on his Facebook account give the impression that he has recently been radicalized or that his Islamist activism has not been fully implemented in his life. Scrolling through his profile, one quickly notes images of an unveiled woman and posts in which he boasts of having Champions League tickets. Yet other imagery he displays is rather more extreme than that of his Facebook friend “Abu Baraa”. Through his Facebook representation, an avatar, Idris has gone virtual – someone online sharing jihadist videos and giving lectures, while at the same time keeping his Facebook friends updated on his daily life.

The display of images glorifying the use of violence is quite common among radical Islamists and could be described as a typical online modus operandi. But traditional imagery is not the only kind used by Facebook fighters in their quest to portray themselves as fighters against Western evils.

“Abu Zakariya al-Andalus” displays a profile picture with an image from Fallout 3, a role-playing game in which the player can create his own character and decide in large part whether to take evil actions or good ones, thereby altering the turn of events in the game. For Abu Zakariya al-Andalus, it appears that the picture he has chosen – of a menacing robot, from the cover of the game – has a deeper meaning. He writes (sic): “Obama pig is a fake program a big virus inshallah machine have strong anti-virus alhamdullilah the name is : Anti-Shirk and is ready to operate.”

The comment is perhaps not clearly formulated. The meaning, however, is quite clear. In the game, players are able to create a character that can wipe out their enemies, and this picture suggests such a scenario for the real world: the creation of a super robot to wipe out the leader of the United States.

The way such virtual jihadists represent themselves online is quite often affected by real-life events. On 15 April 2013, blood and horror swept through the streets of Boston as runners were about to finish a marathon. A pressure cooker exploded, killing three spectators. Hundreds were maimed and wounded. Lives were changed forever. Once again, terrorism had struck America. This time the killers had been radicalized in the United States itself. It was something new and something different. In the days after the suspects were tracked down, journalists delved into their background, researching how they had been radicalized on US soil.

Other people were rejoicing, however. Not long after the bombing, a picture surfaced on social networking sites such as Facebook. The picture was a manipulated image from the video game Grand Theft Auto. It portrayed the hero of the game, now bearing the face of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the younger of the two brothers accused of perpetrating the terrorist attack. The picture surfaced on jihadist social media sites. It was soon to be employed as a profile picture by, amongst others, the well-known Norwegian jihadist Mohyeldeen Mohammad, who had recently returned from a trip to Syria. The same person has on several occasions actively encouraged the killing of kuffar, infidels, in Norway. The manipulated illustration shows Dzhokhar, leaning on a car, gun in his hand.

In the game, stars indicate the “wanted level” of the player at any given time. The more civilians and policemen the player kills, the more stars he attains. In the end, he is followed by helicopters and tanks – not unlike the Tsarnaev brothers, who had thousands of police officers hunting them through the streets of Boston.

Mohyeldeen Mohammad does not reveal exactly why he chose this profile picture. But stepping back from his particular case, it easy to imagine how the story of a carnage creator at the Boston Marathon could bear resemblance, in the head of a Western jihadist, to a video game in which the player can create carnage by shooting and killing police and civilians. A Facebook user who chooses such an image as a profile picture may be expressing admiration of Tsarnaev’s alleged act, or conceivably even a desire to do something similar.

What is the origin of the use of imagery from Grand Theft Auto? An article by Yassin Musharbash in Der Spiegel in 2008 cites online jihadist forums alleging that Grand Theft Auto game designers were inspired by killing methods developed by Al Qaeda.

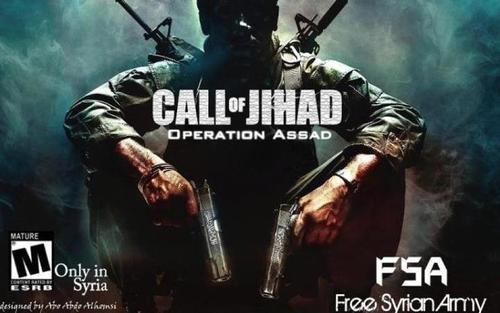

Grand Theft Auto is not the only game referred to by jihadist Facebook users. Another popular one is Call of Duty. This is a one-person shooter game in which the player typically is a US soldier engaged in missions against terrorists and weapon dealers or replaying episodes from WWII. One image in particular became very popular when the Syrian uprising turned into a civil war and the flow of foreign fighters to Syria began, around the winter of 2012. The image portrays a character from the cover of Call of Duty – Black Ops, resting with two guns in hand, and the text altered to “Call of Jihad”. In the left corner another bit of text reads “Only in Syria”. On both guns, Arabic script has been added. The graphic is quite sleek. A Facebook viewer who did not catch the reference to the video game might mistakenly believe the image was an original.

The very title of Call of Duty may explain its popularity in jihadist propaganda. The term wajib, or duty, is central in Islam. Its meaning is similar to fard, which in the Islamic context may be translated into “what is obliged upon the Muslim”.

One of the central ideological beliefs that separate radical Islamists from other Islamic movements is their emphasis on jihad as fard ‘ayn, that is, an “individual obligation”. They differ from traditionalists who would claim that jihad is only an obligation when an amir, or Muslim leader, has declared it. For many Western jihadists on Facebook, there is little doubt: they sense an obligation to aid and fight to advance the cause of their Syrian brethren, not only because the cause is just, but because it is a part of the global jihad to advance the caliphate, the establishment of an Islamic state based only on sharia law.

Perhaps, then, it is not so surprising that these young men turn to cultural references that they are intimately familiar with, like video games. Being a Facebook jihadist is something akin to being a gamer. The Facebook jihadist has stepped into a role, imagining and building his profile to resemble that of a jihadist fighter. Through the profile he is able to act out jihad from the comfort of his own bedroom. He can delve into a fantasy, imagining himself a fighter in the war against kuffar, the disbelievers. Such Internet activity can become a deep-seated habit – waiting for news from the frontier, watching jihadist propaganda being disseminated through media propaganda channels. Sometimes it may also bear a small resemblance to the real thing, as for instance when accounts are hacked or closed down by Facebook for spreading hate speech. Yet, the ultimate danger is not that young Muslims living in Europe may become computer jihadists, but that the call of jihad may be answered in the physical world. Their avatars may tell us something about how that could play out.

Print Friendly

Print Friendly

No comments yet.