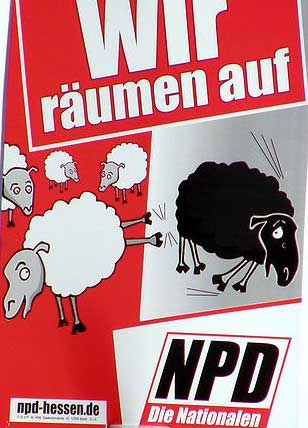

An example of an NPD poster, featuring the text “We’re cleaning up”. The poster was inspired by a similar poster from the Swiss People’s Party (SVP/UDC)

IN DEPTH: “Is Germany’s far-right NPD set to self-destruct?” asks a recent article by Germany’s international broadcaster Deutsche Welle. While the answer is far from given, one of the oldest and more extreme far right parties in Europe is certainly having problems.

Øyvind Strømmen

The National Democratic Party of Germany (Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands) was founded in 1964. It has largely been considered the successor to the Deutsche Reichspartei, but was, in fact, a sort of a catch-all party on Germany’s far right and drew former members of several smaller political parties.

At its inception, few political observers believed the NPH would last long. However, the small party managed to grow. Towards the end of the 1960s, it counted almost 30,000 members, had won representation in seven of 10 West German state parliaments, and was widely expected even to win seats in the German parliament, the Bundestag. It never did. With 4.3 per cent of the vote, the party fell sort of Germany’s 5 per cent threshold for representation. Since then, the NPD – which is described as “anti-Semitic, racist and xenophobic” by Germany’s domestic intelligence agency – has never come close.

From 1971 to 1991, under the leadership of Martin Mussgnug, the party’s role in German politics was negligible. Other far right parties, such as Deutsche Volksunion (DVU) and Die Republikaner, had more success; the latter even made it into the European parliament. The NPD did, however, survive.

In 1991, Günter Deckert took over the leadership. Deckert, who had challenged Mussgnug in the past, and who had left the party for a while, sought a more radical course, bringing neo-Nazi thinking and holocaust denial into the party. In 1995, he was imprisoned after being convicted of hate speech. Udo Voigt took over the leadership and sought to develop closer ties to the country’s non-parliamentarian extreme right, including the neo-Nazi subculture. He followed an activist strategy.

The NPD arranged protest marches that drew considerable crowds – largely skinheads – and its membership increased. In 2006, it entered the regional parliament of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, having managed to clear the threshold in Saxony two years earlier. Both states are in the former East Germany, where the party stands stronger than in former West Germany.

Udo Voigt (left) with the American white supremacist David Duke. Photo: Emmanuel d’Aubignosc / Wikimedia Commons. CC-BY-SA.

Voigt also enjoyed contacts with a number of “white nationalists” internationally, including the notorious American white supremacist, former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard and anti-Semite David Duke. In 2006, Duke interviewed Voigt on his web radio show, presenting him as “the true chancellor of Germany”. Voigt sent his greetings to the world and said that his party was “working to get the control of Germany, but Germany is still an occupied country”.

He also described the number of immigrants in Germany as a “very terrible situation”, and stressed party’s desire to “send the foreigners out”. Later in the interview he states, in rather broken English:

We don’ have a German government. The collaboration people working together with the enemies from the Second World War do not make German politics, they make politics for the winners, but not for Germany.

In the interview, both Duke and Voigt spoke highly of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Earlier that year, the NPD had planned a march through Leipzig in connection with the 2006 Football World Cup; seeking to show its support for the Iranian national team that was playing in the city, as well as for president Ahmadinejad. In the end, the NPD decided to drop the march. On its website, it instead attacked the German national team for not really being German because some team members where of non-German descent.

In 2008, after Barack Obama was elected president of the United States, the party published an article on its website entitled “Africa conquers the White House”. The article, written by Jürgen Gansel, said that the election revealed “the true essence of the American Moloch“, that ‘White America’ was falling apart due to immigration and racial mixing and that the “sprout of Africa” was its “symbolic gravedigger”. The article blamed this on “the American alliance of Jews and Negroes”, and said that Obama’s election victory was essentially a declaration of war, writing in German:

“A non-white America is a declaration of war against all people who see an organically-grown social order based on language and culture, history and heritage to be the essence of humanity. Barack Obama hides this declaration of war behind his penetrating sunshine smile.”

Throughout the years under Voigt’s leadership, the NPD managed to re-establish itself as a major force on the extreme right in Germany, although its political success remained limited to the two state parliaments and a number of local councils. In 2010, a new party platform was adopted, called “Work. Family. Fatherland”. The document might be seen as somewhat watered-down compared to public statements made by the party, but focuses heavily on the Volk (the People), calls for the repatriation of foreigners and equates integration with genocide. It is also strongly anti-globalist, saying that globalization represents the “world dictatorship of Big Capital”, and leads to the “political disenfranchisement, economic exploitation and ethnic destruction [of nations]”. Late that year, the NPD and DVU joined forces.

In 2011, Holger Apfel – a long-time NPD activist and head of the party’s parliamentary group in Saxony – took over as national leader. Apfel sought a new course for the party, and wanted to make it more palatable. For the 2013 federal elections, the party launched an election tour throughout Germany, using a red campaign truck that carried the slogans “Preserve our Homeland. Stop Immigration!” and “We don’t want to be Europe’s paymaster!” The results were a disappointment for the NPD, which received a mere 1.3 per cent of the vote, down from 1.5 per cent in 2009. In mid-December, Apfel stepped down as party chairman, and shortly afterward left the party altogether at a time when, according to Deutsche Welle, “Rumours were rife that he had sexually harassed a male campaign assistant in the run-up to the election.” Apfel himself says that he was the victim of a “personal hate campaign” within the party.

“There’s a lot of internal mudslinging going on,” says the Düsseldorf researcher Alexander Häusler to Deutsche Welle, noting that Apfel’s attempt at steering the party in a new direction “made Apfel a lot of enemies” amongst members “who saw this route as a kind of betrayal of the party’s orientation”. Udo Pastörs, deputy chairman, parliamentary party leader in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and one of the hardliners within the NPD, is now temporarily leading the party. A new chairman will be elected later this year, and Pastörs is a likely candidate. However, a comeback for Udo Voigt – who was maneuvered out of the leadershp by Apfel – cannot be ruled out. Interestingly, both men were convicted of hate speech in 2009, Pastörs after describing Turks as “semen cannons”, Voigt over racist flyers made during the 2006 World Cup. Pastörs also called Germany a republic of Jews (Judenrepublik) and a puppet of “USRael”.

Ironically, one of the few things that can strengthen the NPD at the moment is the fact that the interior ministers of Germany’s 16 states are seeking an outright ban on the party, citing constitutional principles. While German law does allow for banning parties whose operations are deemed unconstitutional, only the constitutional court, the country’s highest, can actually impose such a ban, something it has only done twice. In 1952, the Socialist Reich Party (Sozialistische Reichspartei), a neo-Nazi party, was banned. Four years later, the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) was also banned. A 2003 attempt to ban the NPD was supported by both the government and the parliament, but failed on procedural grounds. Thus, the court never ruled on whether the NPD was in violation of the German constitution.

That failed attempt was an embarrassing blow to the German government, and may have contributed to the NPD’s growth at that time. If this second attempt also fails, the NPD may come away with a new boost, and it will certainly gain publicity for the party. If the banning attempt actually succeeds, the NPD will be gone, but Germany’s right-wing extremist subculture – which has also fostered terrorists – will remain.

Print Friendly

Print Friendly

[…] Voigt has made contact with numerous white nationalists, together with former Ku Klux Klan Wizard and anti-Semite David Duke. In 2006, Duke interviewed Voigt on his net radio present and described him as “the true chancellor of Germany.” Voigt stated that the NPD was “working to get the management of Germany, however Germany is still an occupied country.” […]